How Machines Learn

A grounded explanation of how AI systems learn—and why it's often misunderstood.

On this page

Demystifying How AI Learns

When people hear ‘AI training,’ they often picture secretive laboratories or humming server rooms. Maybe machines plotting their escape. We’ve been primed by decades of science fiction to see artificial intelligence as exotic, even threatening.

The reality is duller. AI training is practice and feedback, repeated millions of times, until a program gets reliably good at a task. That’s it. No mysticism required.

Learning by Adjustment

Machine learning is pattern fitting. An AI model starts with random internal settings, essentially random guesses about how inputs relate to outputs. You show it an example. It makes a prediction. Then it checks how far off that prediction was from the correct answer, and nudges those internal settings to do better next time.

This happens millions or billions of times. Guess, check, adjust. Simple in concept, but powerful when you do it at scale.

The Three Ingredients

Data is the raw material. For image recognition, that’s millions of labeled photographs. For a language model, it’s books, articles, conversations, code. The data defines what the AI can possibly learn. It’s the only window the model has into the world, which turns out to matter a lot.

The model is a network of adjustable numerical values. Mathematicians call them parameters. A useful analogy: think of a mixing board in a recording studio, where each slider shapes the final sound in some small way. Parameters work similarly. Each one influences how the model responds to particular features of its input, and during training, they get tuned until the output is accurate. Or accurate enough.

The loss function keeps score. It measures the gap between what the model predicted and the right answer. Small gap, small adjustment. Big gap, bigger correction. This is the feedback signal that drives learning.

Put these together and you get a feedback loop. Data flows in, predictions flow out, errors get measured, and parameters shift. Do this enough times with enough data, and you end up with something that can recognize faces or translate languages.

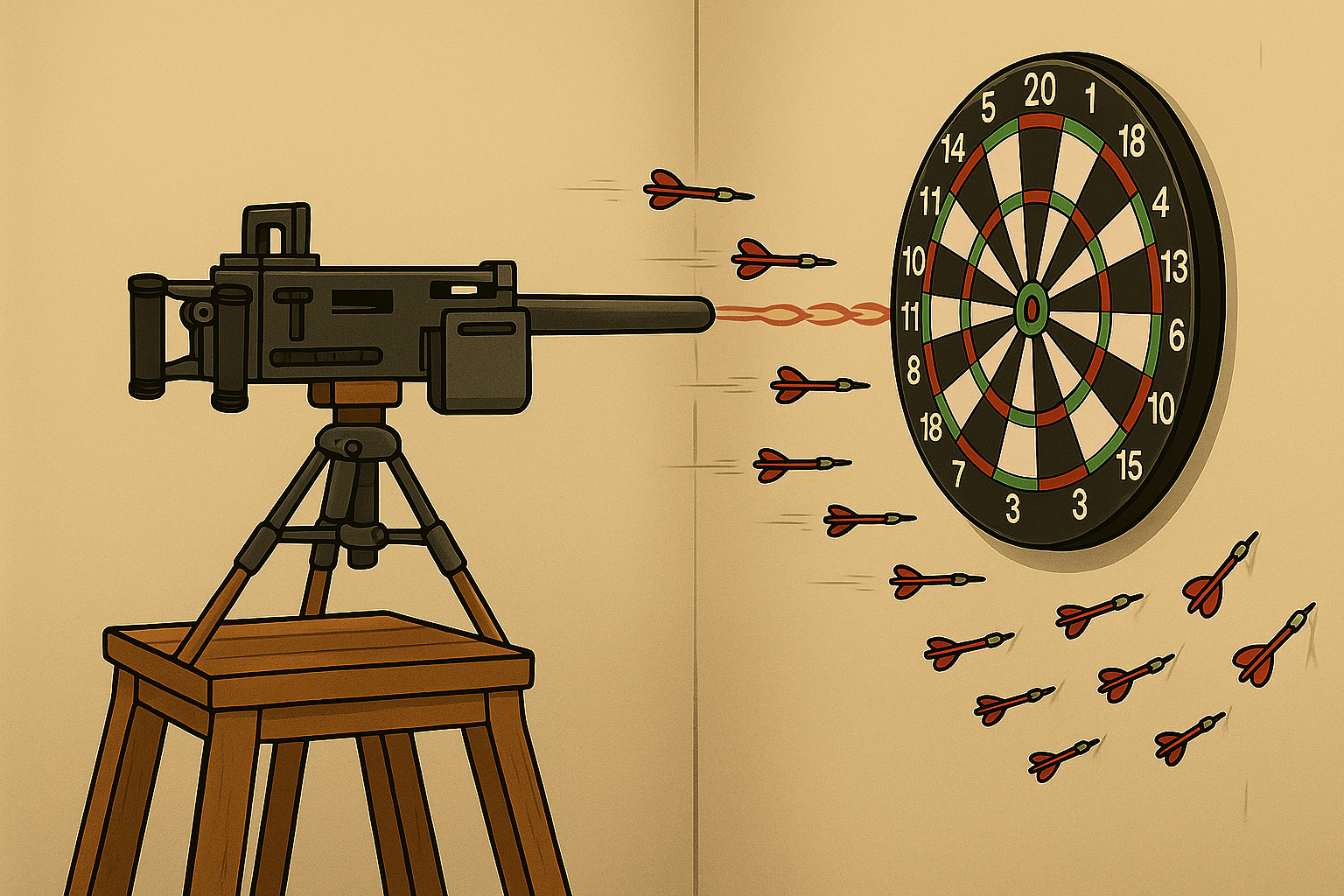

The Dartboard Analogy

Say you’re learning to throw darts. First attempt, the dart sails past the board and punctures the wall. You adjust something (your grip, your release point, how hard you’re throwing) and try again. Over many throws, you start clustering closer to the target.

Here’s what’s interesting: it’s hard to say exactly what you’re adjusting. You feel your way toward better throws. The feedback is obvious (you can see where the dart landed), but the changes you make are almost intuitive. You know what you did, but explaining it to someone else is tricky.

AI training follows the same logic, except the feedback and adjustment happen in numbers, automatically. The model throws a prediction, measures how far off it was, and tweaks its parameters to compensate. The difference is speed. An AI can throw millions of darts per second, adjusting billions of parameters at once. What takes humans years of practice can happen in hours.

Scaling Up

Modern AI systems apply this idea at a scale that’s hard to wrap your head around. The datasets are enormous. Parameter counts reach into the trillions. Training runs burn through staggering amounts of electricity. But strip all that away and the core process is the same: show examples, measure errors, adjust, repeat.

What This Process Doesn’t Do

Despite what headlines suggest, none of this produces anything like human understanding. The model doesn’t comprehend. It doesn’t plan or reflect or have experiences. What it does is adjust mathematical weights to predict patterns in data it has seen before.

When an AI generates something that looks creative or insightful, that’s a reflection of patterns in the training data and objectives its designers chose.

There’s no inner life. Just sophisticated pattern matching, refined through repetition.

Human Fingerprints

Every stage of training involves human choices. Which data to include. What counts as a good prediction. When to stop training. These decisions shape behavior in ways that aren’t always obvious.

Biases in the data become biases in the model. If the training set over-represents certain viewpoints or under-represents others, the model inherits that slant. The machine automates the learning, but humans set the curriculum.

So What?

Strip away the jargon and AI training isn’t mysterious. It’s practice with an automatic scorekeeper. Guess, check, adjust, repeat until the predictions become useful.

Seeing it this way makes the gap between science fiction and reality feel smaller. And maybe that makes the actual achievements more impressive, not less. This simple loop, scaled up, produces systems that can translate languages, spot tumors in X-rays, or carry on a conversation. Not magic. Just math, data, and a lot of repetition.